BALLURIAU Paul, 1860-1917 (France)

What is

The Arabian Nights?

by Michael Lundell

It's a question which permeates any conversation, writing, reproduction, production, translation, interpretation, conversation or statement about anything to do with

The 1001 Nights,

The Arabian Nights,

The Arabian Nights Entertainments, etc. etc. etc.

What is it?

The answer is not so clear and can't be, ever, which is either the 1. frustrating or 2. liberating part of the 1001 Nights.

Much of the academic inquiry into the

Nights seems focused if not obsessed with trying to figure out the history of the

Nights, looking for the “right” answer to the

Nights’ origins which, because of its very nature and history, has eluded everyone who has dared to ask about it.

The

Nights basically seem to be the ultimate jazz-riff on story-telling: a general frame story to bracket it and then you are free to do whatever you like after that, but even this loose definition has issues (Disney’s “

Aladdin” for example, part of the “

Nights”? Yes! And No?!)…

Is the

Nights situated within Western "Orientalism" (both traditional and Saidian) and Western perceptions (and misperceptions of the Middle East)? Yes more than No, but absolutely No too.

Some facts can be narrowed down, however, but even these stand on very shaky ground:

1.

The 1001 Nights is a collection of stories framed by the story of Shahriyar and Scheherazade (names and their spellings vary in different versions but not drastically, though translators like Burton find this point to be especially important) in which Scheherazade tells stories each night to her new husband Shahriyar, dramatically either leaving off the end of the story or insinuating a newer better story to come the next night so that he doesn’t kill her the next morning.

Before he married Scheherazade, Shahriyar had his new brides killed the next morning, because his original wife committed adultery, and he believes women are not to be trusted. He listens to Scheherazade’s stories instead of killing her, however.

- This “fact” is problematic on several levels, take another look at the Disney example – there is no Scheherazade in

Aladdin and yet “Aladdin” is a well established part of the “

Nights” canon, existing as a part of, and even as a separate representation of, the

Nights.

- Also in some versions Scheherazade tells the stories to her sister Dunyazad and Shahriyar listens from the side, permitting his new bride to continue the next day.

1a. (more speculative truths to follow here in 1a!): These stories are thought to have existed in oral form for years before they were written down, told to crowds by storytellers in cafes and marketplaces in the medieval Middle East, though very little evidence exists to really prove this.

In written form there are no clear origins for the stories though many seem to agree that some of them come from Persian (at least the frame story’s characters’ names), ancient Greek, Arabic, Indian and other European sources, though it is impossible to ascertain these origins beyond some general “sense” of where they come from.

2. The earliest (hand written) manuscript versions have been found to originate from Syria and Egypt, written in Arabic. The earliest printed published Arabic versions originated from Egypt and India (printed in Arabic by the British in India).

The first European version

Les Mille et Une Nuits was published in French by Antoine Galland in 1704. An anonymous English translation of Galland titled

Arabian Nights’ Entertainments was published in 1706. There are now “translations” in just about every language on the planet, though what they are translations of would be an interesting starting point to think about when approaching them.

2a. Galland’s version was so popular that Galland’s publisher insisted that Galland, and later other authors writing under Galland’s name, expand the story collection and find more tales to put in. Galland’s version was thus created between 1704 and 1717. Galland himself was interested in finding a “complete” version of the Arabic Nights, containing “all” “1001” tales but he was unable to find such a version.

3. There is no original version and no original author.

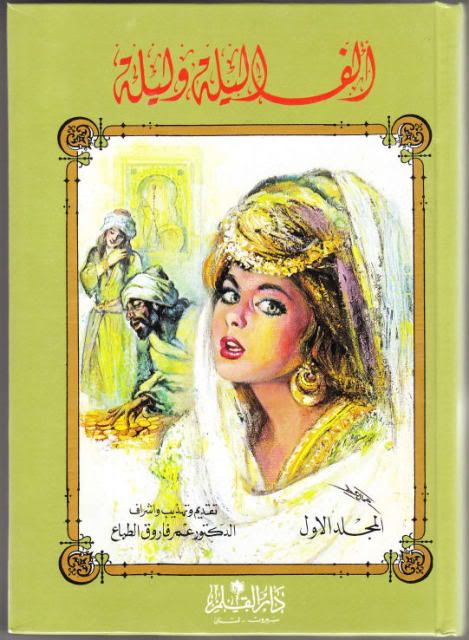

4. The earliest Arabic titles for the collection include

One Thousand Nights and

One Thousand Nights and a Night). Though some versions have no title. The following timeline is compiled largely from

The Arabian Nights Reader listed in the bibliography below so look there for verification of what I’m saying and the other titles are commonly found.

Some historical references to the title:

Late 800s AD – reference to “Alf Layla” (One Thousand Nights) on a paper found by Nabia Abbott

Masudi (900s AD) – mentions a book “One Thousand Nights and a Night” (Alf Layla wa Layla) – also mentions the Persian book “Hezar Efsane” which translates to “One Thousand Stories” (or “Tales”) of which the Arabic book Masudi was looking at was supposedly a translation of. No Persian original has ever been found.

Ibn Al-Nadim (900s AD) – mentions a book “One Thousand Nights” (Alf Layla)

Galland’s Arabic Manuscript (1400-1500s AD) (oldest version of the Nights found to date) – no title? - but has "Alf Layla wa Layla" in between the chapter headings, at least according to the picture on this page, which still is unverified as to what manuscript it really is.

Galland’s French translation (1704) – “Les Mille et une Nuits” (The One Thousand and One Nights)

First English Translation (1705 or 1706) – “Arabian Nights’ Entertainments”

Bulaq (1835ish) - “Alf Layla wa Layla” – One Thousand Nights and a Night

Calcutta II (1839ish) – “Kitab Alf Layla wa Layla” – Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night

5. The first use of the name “Arabian Nights” comes from an anonymous author’s English translation first published in 1705 or 1706 of Antoine Galland’s French version (or what he had translated/written to that date) which started appearing in 1704. The first English version is titled “Arabian Nights’ Entertainments.”

6. Beyond the frame story of Shahriyar and Scheherazade and the titles and general themes of some of the core stories there is often little continuity between versions or translations of the 1001 Nights.

7. Many (arguably the most famous) stories of the 1001 Nights, “Ali Baba” (and the Forty Thieves), “Aladdin,” and “Sindbad,” first appeared in the 1001 Nights in Antoine Galland’s French version. No original Arabic manuscripts for “Ali Baba” or “Aladdin” have ever been found. Galland said he heard some of the stories in his collection from a Syrian man named Hanna Diab. “Sindbad” existed in a separate Arabic manuscript but was not a part of any separate story collection. Galland seems to have inserted “Sinbad” into the 1001 Nights collection himself.

8. The timeline of the Nights’ history is debated but the earliest mention of the Nights is on a scrap of paper that has been dated to the late 800s AD by Chicago scholar Nabia Abbott in 1948. The contents of the paper include the title “Alf Layla” (One Thousand Nights) and mention of the frame story but no stories are printed on the paper.

9. Additional mentions of the story collection appear in the 1100s AD in writings by medieval historians Ibn Al-Nadim and Masudi. These early mentions also reference a Persian book called Hazar Afsaneh (“1000 Tales”) which, Masudi says, the Arabic versions were a translation of. No existing Arabic version of the 1001 Nights before 1400AD nor the Persian story collection “Hazar Afsaneh” have ever been found, however.

10. The earliest existing collection of stories containing the frame story of Scheherazade and Shahriyar and the "core" tales is the three volume set, written in Arabic, in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. This set was part of the original collection that Antoine Galland used for his French translation in 1704. This earliest version has been dated to the 1400s-1500s AD.

In a way, the “Nights” is much more of a concept than an actual book. The title has been used as an adjective in many many many settings and for many reasons. Consider phrases like “something out of the Arabian Nights” or “like a character from the 1001 Nights” and you’ll start to understand the breadth of the usage of the story collection’s title, let alone the stories themselves.

The Nights as a story collection has been talked about and studied using just about any theoretical approach possible: political theory, feminist theory, literary theory, translation theory, psychological theory, etc. Variations of the Nights have been made into literary works including poems, plays, novels, and stories. They have been mentioned in just about every piece of literature you can imagine. The Nights have also been featured prominently as a theme in films, paintings, music, opera, cartoons, board and card games, comic books, video games, political events, cultural representations, city planning and more.

The search for the right answer to the history of the Nights has only led to more questions than answers but is not likely to go away any time soon, nor is it likely to come to any sort of definitive conclusion any time soon.

Maybe the story collection’s elusive nature leads itself to have so many broad applications. The open ended nature of Scheherazade’s tales themselves seems to allow this to happen.

In any event, then, perhaps there are NO misconceptions or misuses of the Nights after all because just about anything is applicable to its name.

I think I’ve covered the main (and only, and shaky) truths that can be said about the Nights so the next time someone talks about them ask them questions: what do you mean? Which version? What story are you talking about? Where did you hear that? Etc…And you’ll come up with some interesting questions/answers/things to look into further.

Remember also when you write or speak about the “Nights” and a particular version or derivative it’s almost as if you are talking about a separate book (the version you are reading) than any representative of the Arabian Nights as a whole. Look into the particulars of whatever version you are studying rather than drawing general conclusions about the Nights as some kind of concrete book with an “original” somewhere, I think it will provide more specific and more fruitful discussion.

That said, every author and scholar of the Nights does have his or her own weird ideas about the existence of the “1001 Nights” as a whole somewhere in the universe as a jumping off point for their own versions and articles and inquiries but they are all based on fantastic speculation, which may be just fine after all.

I'm particularly interested in seeing if any "core" identity of the Nights can be discerned at all, through all of its many mirrored faces, though I'm fairly certain it's a very shaky task.

Whatever you do don’t get involved in some weird cultural debate/chest-thumping contest over the Nights and their origins, you will be 100% wrong whatever you claim unless you claim “nobody knows where these stories are from, they are probably from all places and all times.” Why do I mention this? Check the “1001 Nights” wikipedia discussion page for a fierce debate about the Nights and their origins here as an example:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:One_Thousand_and_One_Nights (I have avoided getting involved in the wikipedia page on the Nights or its debates because it needs so much help I figure I can just write my own page here).

An editorial in the Egyptian newspaper Al Ahram daily has suggested a pro-Persian conspiracy on wikipedia and mentions the Nights:

http://egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com/2009/04/wikipedia-is-iranian-agent.html

For English readers interested in the Nights here is a good list of sources and versions you can take a look at with my own take on them, you can also find in them verification for the facts I’ve presented and further bibliographies should you be interested in pursuing the mad trail of the Nights:

1. Reynolds, Dwight F. "A Thousand and One Nights: a history of the text and its reception." Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period. Eds. Roger Allen and D. S. Richards. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- This is by far the best and most concise history of the 1001 Nights I’ve ever read. You need to get a copy of this and read it if you are interested in the Nights and their history at all. In a future class I’d like to teach on the Nights this would be the first thing I’d have students read. This book might be hard to get (ie expensive) if you are not affiliated with a university library and can check it out but it might be worth a local university library membership if you are interested. Most university libraries will let you enter and photocopy (for a small per page fee) without affiliation, however.

1.5 Nurse, Paul.

Eastern Dreams: How the Arabian Nights Came to the World. Penguin. 2010.

A complete and straightforward introduction to the textual history of the

Nights, one of the best books on the subject and part of the

Nights canon, to be sure, for years to come. This book is especially important as it gets into the details of Galland's life and his publication of the

Nights, which does not exist at any length elsewhere in English.

2. Ross, Jack. “A new translation of the Arabian Nights.”

http://mairangibay.blogspot.com/2008/12/new-translation-of-arabian-nights.html

This is a free online article and great introduction to the various English language versions of the 1001 Nights and their histories and differences. A must read for anyone interested in seeing what version they should start reading.

3. “The Arabian Nights Reader.” Book edited by Ulrich Marzolph, 2006. This reader has several important scholarly articles on the history of the Nights including Nabia Abbott’s study of the papers she found in 1948 and a short essay on the history of the titles. Other articles are hit and miss but the book is important for the historical articles.

4. Read the introductions to the online versions I have linked here or any introduction to the Nights and you’ll get a feel for the variations of the Nights and what each author thinks of their history.

5. If you are looking for a version of the Nights to buy and are discouraged by seeing Richard Burton’s 16 volume edition with footnotes and crazy language, never fear, there are several decent and smaller versions that can give you at least a taste of the Nights.

Both of these are fairly inexpensive on Amazon and will certainly give you plenty to work with:

NJ Dawood’s “Tales from the Arabian Nights.” Penguin. Despite having many problems with the author’s introduction this version is quite readable and in my opinion better written than the Haddawy translation. Although again, it is very problematic on its own but so is every version. This is a very small selection of the Nights but its prose is also quite readable and it contains most of the popularly known stories.

Robert Mack, editor:

Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Oxford World's Classics. This is the “complete” English translation of Galland’s French version (as Galland's version looked in 1705 before later additions), all in one volume, quite a big paperback but not too huge to hold. This version’s language holds up quite well over the years and is surprisingly accessible even to the contemporary reader and includes the crowd favorites “Ali Baba,” Sindbad,” and “Aladdin” as they were first read in English in 1705/1706. Of course you can download this version too for free on Google books but it’s probably cheaper just buying a cheap copy on Amazon than printing it or messing up your eyes by reading it online!

Robert Mack's introduction in this volume is also a great historical account of the Nights and its timeline is written in a straight-forward and readable manner.

6. Jorge Luis Borges, “The Translators of the Arabian Nights.” This is a somewhat abstract article (in Borgesian fashion) on the different versions of the Nights and makes for an interesting and poetic theoretical approach to the Nights.

7. Mia Gerhardt. “The Art of Story Telling.” This is a difficult academic book to find but it does a good job of introducing the history of the Nights and also has some interesting literary takes on the Nights stories in general. A sort of must-have in the canon.

8. Robert Irwin. “The Arabian Nights: A Companion.” This book is interesting and is somewhat of a canonical text vis-à-vis the Nights. Though it feels a bit unfocused at times the book attempts to cover just about everything regarding the Nights you can think of (history, reception, setting, influences, etc.). The most interesting part of this book to me is the historical information about medieval Cairo and its crime stories and their relationship to some of the stories in the Nights.

There are about three tons of literature and scholarship on the Nights, check out my “free articles” link on this blog and you will find some online bibliographies that are a good starting point for investigating the Nights phenomenon academically.

Thanks, feel free to add your own 2 cents and book recommendations below,

- ML