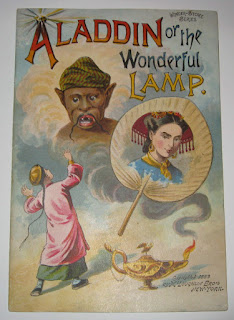

Aladdin's Picture Book Arabian Nights, Illustration by Walter Crane, 1878

There are a bunch of great reviews out on

Visions of the Jinn, here are excerpts of and links for two:

Many thanks to Ghada for passing along this review of Robert Irwin's new book on the illustrations/illustrators of the

Nights from brainpickings.org.

Irwin's book is currently only in hardcover format and costs almost $200.

Here's part of the review, it has great pictures from the book so do visit their site, this review was reprinted in the Atlantic Monthly too, but don't know the connection between brainpickings and the Atlantic.

Link:

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2012/01/20/visions-of-the-jinn-arabian-nights-illustrations/

From the review: "Even though the editions since Lane’s scholarly translation had progressed in the realm of visual imagination, the content had remained rather sterilized and prudish. It wasn’t until the 1885-1888 publication of

Richard Burton’s sixteen-volume translation that themes of sexuality emerged, complete with extensive notes on topics like homosexuality, bestiality, and castration. Though Burton’s original edition featured no pictures in order to avoid prosecution for obscenity, shortly after his death in 1890 a young friend and admirer of his by the name of

Albert Letchford, who had trained in Paris as an orientalist painter, created 70 paintings, which eventually became the basis for the next edition of Burton’s translation. With a keen sensibility for fantasy and a shared interest in the erotic to complement Burton’s own, Letchford’s artwork featured many nudes and were infused with sensuality. Ironically, Letchford contracted an exotic disease in Egypt and died at a young age."

------------------------------------------------------------------

Here is a more extensive review from the

TLS, many thanks to Moti for passing this along, I've excerpted bits of it below, for the entire review see:

http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article858481.ece

Visions of the Arabian Nights

Elizabeth Lowry

Robert Irwin

VISIONS OF THE JINN

Illustrators of the Arabian Nights

240pp. The Arcadian Library. £120 (US $225).

978 0 19 959035 3

Published: 18 January 2012

"Nowhere is the fascination felt in Western culture for the East more evident than in its avid consumption of The Arabian Nights. Ever since Antoine Galland issued the first translation in French in the early eighteenth century, the stories have become a permanent part of the Western literary and visual landscape, spawning numerous adaptations, tributes and imitations. Princess Scheherazade, Aladdin, Sinbad the sailor and Ali Baba have acquired the status of cultural icons; genies, flying carpets and magic lamps, once curiosities of medieval Arab and Persian mythology, are now the stock-in-trade of modern occidental fantasy. There have been musical interpretations of the tales by Rimsky-Korsakov and Weber; cartoon versions by Disney, and lavish Hollywood incarnations. The influence of the Nights extends from the poetry of Goethe to Wordsworth to Rilke, to modern fiction from Fielding through Proust to Borges. In fact, so much of European and American literature has been influenced by the tales that it would be far easier, as Robert Irwin suggests in his The Arabian Nights: A companion (1994), simply to list the handful of writers who were not influenced by them.

Irwin returns to the theme in this sumptuous history of the illustrated Western editions of The Arabian Nights. Visions of the Jinn is part bibliographical exposition, part dazzling magic lantern show: its 164 colour-saturated facsimiles, photographs and black-and-white images and their accompanying analysis offer a visually stunning and sensitive account of the European response to this important text.

How Arabian are these nights? Although we have come to associate them with Arab culture, the tales are properly speaking a composite work deriving from the oral traditions of India, Persia, Iraq and medieval Egypt. The first written version is a Persian collection translated into Arabic some time in the early eighth century as Alf Layla, or “The Thousand Nights”, although the number of tales included fell well short of that (in Arabic, alf simply denotes a large quantity). The title The Thousand and One Nights (probably from the Turkish expression bin-bir, “a thousand and one”, which is again suggestive rather than exact) became attached to the text in the twelfth century. To this core stories were later added, until the work delivered on the promise in its title. The European translations that followed after Galland produced his courtly twelve-volume Les Mille et Une Nuits in 1704 differed in quality and in their unspoken agendas. The best known are by Edward Lane, Richard Burton and Joseph Charles Victor Mardrus. Lane’s translation (1839–41) is scholarly but prudish, and heavily bowdlerized to eliminate any sexual references that might offend its Victorian readers; Burton’s (1885) takes the opposite approach, ramping up the raunch; while reading Mardrus (1902) is rather like spending an afternoon with a slightly louche uncle who manages to combine whimsy with constant suggestiveness."

"The stories told by Shahrazad draw on a seemingly inexhaustible range of subjects. They are heroic, fantastical, comic, pious, obscene, tragic, didactic, brutal and sentimental in turn – quite a challenge to an illustrator. Some crack along at a tremendous pace and others fall prey to longueurs as Shahrazad meditates on knotty problems of philosophy or abstruse ethical questions (there is an intriguing insight here into what counts as a page-turner in medieval Persia: Shahrazad thinks nothing of including, say, asides on law and human physiology, confident that Shahriyar won’t summarily reach for the axe). The way in which the illustrators of the Nights chose to represent their subject matter, however, inevitably says as much about them as about it. In the eighteenth century, Western artists imagining the East had limited visual resources to draw on: prints of the costumes and peoples of the Orient by those who had actually been there were scarce, and the same sets tended to do the rounds – sixty Turkish drawings by Nicolas de Nicolay were a particularly popular source, and were still being used by Ingres early in the nineteenth century. In the frontispieces of this period, as Irwin points out, Shahriyar and Shahrazad often appeared in bed – but “invariably a nice, solid European bed”. It was not that the illustrators of the Enlightenment weren’t alive to the sexual and seductive overtones of the stories, but the emphasis was firmly on decorum. David Coster’s frontispiece for Galland’s edition shows the royal couple tucked up under a baldachin beneath a neo-classical ceiling. The demure-looking Shahrazad, in a French gown of fashionable eighteenth-century cut, is clearly in the middle of one of her more earnest disquisitions on faith and morals, although her breasts are incongruously bare. Just as the beds were European, so “the landscapes were commonly western and pastoral”. Sinbad and Ali Baba may wear turbans but they are dressed in togas, posing in front of classical ruins, or strolling in breeches through English woods.

It was only towards the middle of the nineteenth century that a broader and more reliable range of visual material about Arab and Turkish life was made available, and the illustrated editions of the Nights from this time begin to have pretensions to visual scholarship. Edward Lane’s three-volume, heavily annotated translation had a self-consciously didactic purpose, aiming to introduce readers to the Middle Eastern way of life. The pictures by William Harvey were intended to have an educative function, serving as the visual flourish to Lane’s learning, and their accuracy was vouched for by the translator himself. In fact, they were supposed to be even more accurate than the source material – as Lane assures the reader in his preface, thanks to his vigilance in standing over the artist and hectoring him with tips, the latter “has been enabled to make his designs agree more nearly with the costumes &c. of the times which [the] tales generally illustrate than they would if he trusted alone to the imperfect descriptions which I have found in Arabic works”. Unsurprisingly, Harvey’s boxwood engravings, though delicate and replete with authentic detail, are rather insipid."