arabian nights dance hit from europe, the band is chipz from the netherlands

i can hear it loud and clear playing in a place like the no bar in quito, ecuador, babylon disco ayia napa, or the like

Monday, December 29, 2008

Sunday, December 21, 2008

financial times review of lyons' version - as byatt

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/c51a2b54-cbcd-11dd-ba02-000077b07658.html

The Arabian Nights

Review by AS Byatt

Published: December 20 2008 01:13 | Last updated: December 20 2008 01:13

The Arabian Nights

Translated by Malcolm C Lyons (3 volumes)

Penguin Classics £125

FT Bookshop price: £100

Wordsworth, as a child, had “a little yellow canvas-covered book, a slender abstract of the Arabian Tales”, which fed his imagination. He describes the “promise, scarcely earthly” of discovering that there were four large volumes of the tales. Coleridge said that his mind had been “habituated to the vast” by his early reading of “Romances and Relations of Giants and Magicians & Genii”. Opening this wonderful, orderly new translation of the Arabic Calcutta II manuscript made me feel Wordsworth’s excitement over again. Malcolm C Lyons has put the stories into clear, readable English, and has not omitted the poems that decorate and deepen many of the texts. Each volume has an introduction by Robert Irwin, whose The Arabian Nights: A Companion is both wise, witty and informative. Two of the best-known tales, “Ali Baba” and “Aladdin” are known as orphan tales, since there is no extant Arabic version. These have been translated, by Ursula Lyons, from the 18th-century French of Antoine Galland.

Human beings are narrating animals. We construe our lives as stories, we recount other people’s lives to each other, in gossip, in history, in literature. One of the oddest literary enterprises was the modernist attempt to make novels that did not tell stories. It can’t really be done. Stories end with death, though we also tell stories about time after death, pious or horrific, heavenly pleasures or lurking vampires. The chief glory of the Nights is the form of its frame story. King Shahriyar is maddened by his wife’s adultery with black slaves. He kills her, and marries a new virgin daily. She is enjoyed and put to death in the morning so that she will betray no one. The Vizier has a daughter, Scheherazade, wise and beautiful, who begs her father to marry her to the king as she has a plan to put a stop to the destruction of young women. She asks for her young sister, Dunyazade, to be brought to the bedchamber, and after Scheherazade has been deflowered her sister asks for a story. It is unfinished at dawn, and the king desires to know the end, so spares the storyteller. But the next story, and a thousand and one stories, linked like chains, contained in each other like boxes in boxes, sprouting like twigs out of branches, continually defer death. Three children are born during the storytelling and, finally, the queen is allowed to live. Scheherazade is one of the great heroines who inhabit our imagination. Practical, dauntless, courteous, she saves her world again and again.

This is strange in some ways, as the world of the Nights is very male. The tales, as Robert Irwin tells us, were told by men to men, merchants in bazaars, shopkeepers, interested in trade, inhabiting narrow streets. They depict women as dangerous, treacherous and unscrupulous – one is entitled “The Craft and Malice of Women”. Their world is, as Irwin also points out, full of things – containers, jars, pots, gold and silver, things bought in markets. It is full of meetings between porters, disguised caliphs, veiled women, scholars, all of whom have a tale to tell, which contains another tale, or provokes its audience into telling their own.

Coleridge was very impressed by the tale of the merchant who casually threw away a date stone, and was immediately arrested by a furious ifrit (or genie) who said that the stone had killed his invisible son. The merchant’s execution is delayed so that he may put his affairs in order. When he returns to keep his appointment with his executioner his life is saved by a series of storytelling passers-by. Coleridge saw the date stone as an example of pure chance, operating in a world where chance was the same as destiny, and said it gave him the idea for the ineluctable world of the tale-telling Ancient Mariner. Things happen at random, and are simultaneously fated and unavoidable. The man who fled death by going to Samarra, only to find that death was waiting for him there, is only one example. Irwin has written about the way in which characters in these tales don’t have what we should think of as “character” – they are their fate or their story – Sindbad is the things that happen to him. When the tale is finished they drop back into dailiness and disappear.

The tales are sweet, sad, obscene and marvellous. Things shift shapes – men and women are changed to dogs, to cows, to gazelles, or turned to stone from the waist down. The jinn, creatures made of fire and smoke, appear and disappear. Some are godfearing. Some are satanic. Some haunt lavatory doors. In the splendid tale of Quamar al-Zaman two of these beings, one female, one male, get into a dispute over whether the young prince or the princess of the Chinese Islands is the more beautiful, and transport the sleeping girl across oceans to the prince’s bed, calling up a third hideous ifrit to help adjudicate. They can be sealed into jars or bottles from which they can rise like smoke to tower in the sky. The tales, like the jinn, both tease and satisfy the imagination.

AS Byatt is the author of ‘A Whistling Woman’ (Vintage) and co-editor of ‘Memory: An Anthology’ (Chatto & Windus)

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Monday, December 15, 2008

On a sea of stories - New Statesman Review of Lyons' 1001 Nights

http://www.newstatesman.com/books/2008/12/arabian-nights-stories-arabic

Books

On a sea of stories

Hugh Kennedy

Published 11 December 2008

The stories of The Arabian Nights are so famous that most of us have never read them, but just absorbed them as nursery tales or cartoons. Now a new translation, the first in more than a century, allows us to enjoy the vast original

Fantastic voyage: Charles Folkard’s 1917 illustration to The Third Voyage of Sinbad the Sailor in The Arabian Nights

The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1,001 Nights

Translated by Malcolm C Lyons with Ursula Lyons Introduced and annotated by Robert Irwin

Penguin Classics, three vols, £125

We have all heard of The Arabian Nights, most of us probably as children's stories and cartoon films. The most famous have become stock images of English writing - the genie in the bottle; the door that responds to the cry of "Open Sesame!". Perhaps the most famous of all is the story of Aladdin and his magical lamp, one of the traditional pantomime plots. How many times have we heard policemen describing entering some criminal's storeroom and saying, "It was like an Aladdin's cave in there"? But there is much more to The Arabian Nights than that, and now, in effect for the first time, the English reader can appreciate the full, vast extent of this "ocean of stories".

The "Nights" as we have them today are the product of more than a thousand years of evolution, development and accretion. The original tale, in which Shahrazad tells stories to the jealous king so that he will not put her to death, comes from a Sanskrit original produced in India, probably in the first centuries AD. This was translated into Middle Persian (that is the language of Sasanian Iran, c.220-650 AD) and many more stories of a moralising and improving, if slightly dull, sort were added. Like much of the literary heritage of pre-Islamic Iran, the originals of these stories have disappeared, but soon after the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, they were translated into Arabic.

One page of a 9th-century version survives, which is enough to show that Shahrazad was already telling stories. Although we know that the Nights continued to be developed and elaborated, the earliest substantial manuscript we have dates from the 15th century.

The Arabian Nights essentially reflect the world of Egyptian and Syrian urban culture of the Mamluk period (1260-1517) and the heroes of the stories are as often merchants as kings and princes, something that would be unimaginable in the contemporary world of Arthurian romance. There is lots of talk of commerce and money, the everyday life of the souks and ports from which the unsuspecting, but not unwilling, merchant can be lured to unimaginable adventures. Some of tales are set in clearly defined historical contexts. The most famous of these are the ones featuring the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786-809), the vizier Ja'far the Barma kid, Harun's wife Zubayda and the poet/court jester Abu Nuwas. These are all well-known historical figures but none of the stories in which they figure has any known historical basis, and the caliph's night-time, incognito wanderings through his mysterious capital of Baghdad are no more than devices to introduce more fabulous events. In most cases the stories are set in a sort of never-never land, just far enough beyond the horizons of the familiar world to allow for marvels and wonders of all sorts.

It is fair to say that the Nights was looked down on, or more often simply disregarded, by the literary elite of the Arabic-speaking world. The simple narrative flow, the numerous marvels and wholly improbable events, the questionable morality and, perhaps most of all, the sex with which the "Nights" are, to use Robert Irwin's expression, "suffused", all combined to ensure that they were never part of the classical Arabic canon.

There are many Arabic epics, some at least as long (that is, about a million words), but none of them has achieved the popularity and widespread circulation of the Nights. This is at least in part because most of the other epics consist of endless accounts of wearisome battles in which resolute but entirely one-dimensional heroes achieve impossible feats of arms. What distinguishes the Nights and, despite its great length, stops it from becoming tedious, is the different registers of story - comic, romantic, sad, adventurous. It is impossible to predict the twists and turns, and, embarking on any of the stories or cycles of stories, the reader can have no idea where he or she is going to end up.

The most typical narrative device is, of course, the story within the story, in which the lead story of the sequence is repeatedly interrupted as the hero meets people (or animals or jinns) who have their own tales to tell, or when people staying awake at night begin to tell the stories of their lives. No one is ever told to shut up in the Nights: if there are eight brothers, each with a story to tell, they must all have their say. Equally intriguing is the way in which the narrative, after wandering serendipitously in many different directions, gradually brings you back to the main thread and the reader feels that little jolt of recognition: "So that's how we got there."

The variety of The Arabian Nights and its light-hearted and entertaining style has made it better known in the west than any other work of Arabic literature. But, in a very interesting way, the "Nights" as we know them are the product of a creative interaction between the Arabic text and the French and later English translations. Between 1704 and 1717 a version of the Nights was translated into French by Antoine Galland and became an immediate success. Galland's translation was elegant, sentimental and, like most of the translations that were to follow, heavily bowdlerised, but its popularity ensured there would be further translations into more languages. Galland was also the author of some of the classic stories that we think of as integral parts of the work. There are no Arabic originals of the stories of Ali Baba and Aladdin. Galland claimed that he was told them by a Syrian visitor but he may equally well have made them up himself. However, they sit very well with the rest of the collection, to the extent that Arabic translations have now been made and integrated into the text.

The translations that followed Galland were popular with the reading public but none of them provided a satisfactory rendering of the original. The first English translation directly from the Arabic (rather than from Galland's French) was made by E W Lane in 1838-41, but it was incomplete, bowdlerised and written in a ponderous, old-fashioned prose that in no way reflected the simple narrative tone of the Arabic. Much more famous was the translation made by Sir Richard Burton and published, in 16 volumes, between 1885 and 1887. Burton relished all the erotic and bizarre material that Lane had edited out, but he, too, succumbed to the temptation to invent a heavyweight and convoluted English prose that makes his version very difficult to read for pleasure.

The new translation by Malcolm Lyons, formerly Sir Thomas Adams's Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, manages to avoid all these pitfalls. This is a truly magnificent achievement. There are some 2,800 pages and exactly 1,001 "Nights", all newly translated from the fullest Arabic text, the so-called Calcutta II of 1841. As an extra bonus, Ursula Lyons has translated Galland's original stories of Aladdin and Ali Baba from the French. The prose style is simple and clear but never dull. It reads easily enough to be enjoyable light reading, which is exactly as it should be, so that anyone can, as Robert Irwin says in one of his prefaces, "lose themselves in a veritable sea of stories". Irwin is a great authority on the Nights (his Arabian Nights: a Companion is essential for anyone who wants to know more about the book) and his short introductions to each of the three volumes give a clear and lucid setting of the scene.

There are maps and a glossary but otherwise the text is unburdened by the sort of academic apparatus that both Lane and Burton used to show that their translations were serious academic works. Finally, Penguin Books must be congratulated for the elegant production of these three volumes, which make an excellent, if fairly expensive, presentation set. One hopes that there will soon be an ordinary paperback edition of the whole at a more affordable price.

Despite their immense length, the volumes can certainly be read for pleasure and relaxation. True, an attempt to read them all at once would surely provoke literary indigestion. But they should rather be dipped into, as one might dip into a good diary. Once having begun, the reader can easily be swept along and, like King Shahriyar, be so consumed by the desire to know what happens next, that he or she will be compelled to move on to just one more "Night", and another one, two or three after that.

Hugh Kennedy is professor of Arabic at the School of Oriental and African Studies

COMMENTS AS OF 12-15-08

4 comments from readers

sweety

12 December 2008 at 01:15

This is one of the most racist books ever written and gives a spectre grey insight into the Arab Psyche. I guess this translation, unlike mine, will be heavily sanitised. Your freudian slip has been to include the illustration from the book without much thought. Analyse this!

William

12 December 2008 at 19:31

I remember hearing about these these Tales Of the Arabian Nights when i was a child many years ago. Raciam & idealogy was never potrayed, they are just tales to entertain in the wee dark hours of the night. Thats all, the current phase of being clever is self defeating. Just enjoy the prose & skills of storytelling Amen.

swatantra nandanwar

13 December 2008 at 17:50

I'm sure you'd find 'racist' comments in Beowolf and Piers Ploughman if you looked hard enough. The Arabs had their class system in the same way that Hndus had their caste system.

Avatar

15 December 2008 at 03:30

I do own a set of the numbered edition of the first Richard Burton edition, published originally for his "book club" and limited to 1,000 sets of numbered sets for his subscribers.

It is a fabulous book, a real masterpiece.

A book that was written in a different time and era and as such, it can not be critiqued by the social rules of today or in the light of political correctness!

Further, if you need to demonstrate the typical class system, you needn't bring the Arabs or Hindus into the conversation, as examples! You have more than enough examples right in your own backyard. You can raise the example of classicism by taking a closer look at your very own British Monarchy and the British Aristocracy all the way to your House of Lords.........Your Aristocrats are not too keen on inviting commoners into their social circles or into their families. So there is no need for you good folks to be looking for examples by pointing over the horizon to find a rigid and fossilized class system!

Books

On a sea of stories

Hugh Kennedy

Published 11 December 2008

The stories of The Arabian Nights are so famous that most of us have never read them, but just absorbed them as nursery tales or cartoons. Now a new translation, the first in more than a century, allows us to enjoy the vast original

Fantastic voyage: Charles Folkard’s 1917 illustration to The Third Voyage of Sinbad the Sailor in The Arabian Nights

The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1,001 Nights

Translated by Malcolm C Lyons with Ursula Lyons Introduced and annotated by Robert Irwin

Penguin Classics, three vols, £125

We have all heard of The Arabian Nights, most of us probably as children's stories and cartoon films. The most famous have become stock images of English writing - the genie in the bottle; the door that responds to the cry of "Open Sesame!". Perhaps the most famous of all is the story of Aladdin and his magical lamp, one of the traditional pantomime plots. How many times have we heard policemen describing entering some criminal's storeroom and saying, "It was like an Aladdin's cave in there"? But there is much more to The Arabian Nights than that, and now, in effect for the first time, the English reader can appreciate the full, vast extent of this "ocean of stories".

The "Nights" as we have them today are the product of more than a thousand years of evolution, development and accretion. The original tale, in which Shahrazad tells stories to the jealous king so that he will not put her to death, comes from a Sanskrit original produced in India, probably in the first centuries AD. This was translated into Middle Persian (that is the language of Sasanian Iran, c.220-650 AD) and many more stories of a moralising and improving, if slightly dull, sort were added. Like much of the literary heritage of pre-Islamic Iran, the originals of these stories have disappeared, but soon after the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, they were translated into Arabic.

One page of a 9th-century version survives, which is enough to show that Shahrazad was already telling stories. Although we know that the Nights continued to be developed and elaborated, the earliest substantial manuscript we have dates from the 15th century.

The Arabian Nights essentially reflect the world of Egyptian and Syrian urban culture of the Mamluk period (1260-1517) and the heroes of the stories are as often merchants as kings and princes, something that would be unimaginable in the contemporary world of Arthurian romance. There is lots of talk of commerce and money, the everyday life of the souks and ports from which the unsuspecting, but not unwilling, merchant can be lured to unimaginable adventures. Some of tales are set in clearly defined historical contexts. The most famous of these are the ones featuring the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786-809), the vizier Ja'far the Barma kid, Harun's wife Zubayda and the poet/court jester Abu Nuwas. These are all well-known historical figures but none of the stories in which they figure has any known historical basis, and the caliph's night-time, incognito wanderings through his mysterious capital of Baghdad are no more than devices to introduce more fabulous events. In most cases the stories are set in a sort of never-never land, just far enough beyond the horizons of the familiar world to allow for marvels and wonders of all sorts.

It is fair to say that the Nights was looked down on, or more often simply disregarded, by the literary elite of the Arabic-speaking world. The simple narrative flow, the numerous marvels and wholly improbable events, the questionable morality and, perhaps most of all, the sex with which the "Nights" are, to use Robert Irwin's expression, "suffused", all combined to ensure that they were never part of the classical Arabic canon.

There are many Arabic epics, some at least as long (that is, about a million words), but none of them has achieved the popularity and widespread circulation of the Nights. This is at least in part because most of the other epics consist of endless accounts of wearisome battles in which resolute but entirely one-dimensional heroes achieve impossible feats of arms. What distinguishes the Nights and, despite its great length, stops it from becoming tedious, is the different registers of story - comic, romantic, sad, adventurous. It is impossible to predict the twists and turns, and, embarking on any of the stories or cycles of stories, the reader can have no idea where he or she is going to end up.

The most typical narrative device is, of course, the story within the story, in which the lead story of the sequence is repeatedly interrupted as the hero meets people (or animals or jinns) who have their own tales to tell, or when people staying awake at night begin to tell the stories of their lives. No one is ever told to shut up in the Nights: if there are eight brothers, each with a story to tell, they must all have their say. Equally intriguing is the way in which the narrative, after wandering serendipitously in many different directions, gradually brings you back to the main thread and the reader feels that little jolt of recognition: "So that's how we got there."

The variety of The Arabian Nights and its light-hearted and entertaining style has made it better known in the west than any other work of Arabic literature. But, in a very interesting way, the "Nights" as we know them are the product of a creative interaction between the Arabic text and the French and later English translations. Between 1704 and 1717 a version of the Nights was translated into French by Antoine Galland and became an immediate success. Galland's translation was elegant, sentimental and, like most of the translations that were to follow, heavily bowdlerised, but its popularity ensured there would be further translations into more languages. Galland was also the author of some of the classic stories that we think of as integral parts of the work. There are no Arabic originals of the stories of Ali Baba and Aladdin. Galland claimed that he was told them by a Syrian visitor but he may equally well have made them up himself. However, they sit very well with the rest of the collection, to the extent that Arabic translations have now been made and integrated into the text.

The translations that followed Galland were popular with the reading public but none of them provided a satisfactory rendering of the original. The first English translation directly from the Arabic (rather than from Galland's French) was made by E W Lane in 1838-41, but it was incomplete, bowdlerised and written in a ponderous, old-fashioned prose that in no way reflected the simple narrative tone of the Arabic. Much more famous was the translation made by Sir Richard Burton and published, in 16 volumes, between 1885 and 1887. Burton relished all the erotic and bizarre material that Lane had edited out, but he, too, succumbed to the temptation to invent a heavyweight and convoluted English prose that makes his version very difficult to read for pleasure.

The new translation by Malcolm Lyons, formerly Sir Thomas Adams's Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, manages to avoid all these pitfalls. This is a truly magnificent achievement. There are some 2,800 pages and exactly 1,001 "Nights", all newly translated from the fullest Arabic text, the so-called Calcutta II of 1841. As an extra bonus, Ursula Lyons has translated Galland's original stories of Aladdin and Ali Baba from the French. The prose style is simple and clear but never dull. It reads easily enough to be enjoyable light reading, which is exactly as it should be, so that anyone can, as Robert Irwin says in one of his prefaces, "lose themselves in a veritable sea of stories". Irwin is a great authority on the Nights (his Arabian Nights: a Companion is essential for anyone who wants to know more about the book) and his short introductions to each of the three volumes give a clear and lucid setting of the scene.

There are maps and a glossary but otherwise the text is unburdened by the sort of academic apparatus that both Lane and Burton used to show that their translations were serious academic works. Finally, Penguin Books must be congratulated for the elegant production of these three volumes, which make an excellent, if fairly expensive, presentation set. One hopes that there will soon be an ordinary paperback edition of the whole at a more affordable price.

Despite their immense length, the volumes can certainly be read for pleasure and relaxation. True, an attempt to read them all at once would surely provoke literary indigestion. But they should rather be dipped into, as one might dip into a good diary. Once having begun, the reader can easily be swept along and, like King Shahriyar, be so consumed by the desire to know what happens next, that he or she will be compelled to move on to just one more "Night", and another one, two or three after that.

Hugh Kennedy is professor of Arabic at the School of Oriental and African Studies

COMMENTS AS OF 12-15-08

4 comments from readers

sweety

12 December 2008 at 01:15

This is one of the most racist books ever written and gives a spectre grey insight into the Arab Psyche. I guess this translation, unlike mine, will be heavily sanitised. Your freudian slip has been to include the illustration from the book without much thought. Analyse this!

William

12 December 2008 at 19:31

I remember hearing about these these Tales Of the Arabian Nights when i was a child many years ago. Raciam & idealogy was never potrayed, they are just tales to entertain in the wee dark hours of the night. Thats all, the current phase of being clever is self defeating. Just enjoy the prose & skills of storytelling Amen.

swatantra nandanwar

13 December 2008 at 17:50

I'm sure you'd find 'racist' comments in Beowolf and Piers Ploughman if you looked hard enough. The Arabs had their class system in the same way that Hndus had their caste system.

Avatar

15 December 2008 at 03:30

I do own a set of the numbered edition of the first Richard Burton edition, published originally for his "book club" and limited to 1,000 sets of numbered sets for his subscribers.

It is a fabulous book, a real masterpiece.

A book that was written in a different time and era and as such, it can not be critiqued by the social rules of today or in the light of political correctness!

Further, if you need to demonstrate the typical class system, you needn't bring the Arabs or Hindus into the conversation, as examples! You have more than enough examples right in your own backyard. You can raise the example of classicism by taking a closer look at your very own British Monarchy and the British Aristocracy all the way to your House of Lords.........Your Aristocrats are not too keen on inviting commoners into their social circles or into their families. So there is no need for you good folks to be looking for examples by pointing over the horizon to find a rigid and fossilized class system!

The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights - the Sunday Times review

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/fiction/article5331420.ece

From The Sunday Times December 14, 2008

The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights - the Sunday Times review

A fresh translation of the world’s greatest collection of folk stories restores their colour and verve

Christopher Hart

“In the royal palace there were windows that overlooked Shahriyar’s garden, and as Shah Zaman was looking a door opened and out came 20 slave girls and 20 slaves, in the middle of whom was Shahriyar’s very beautiful wife. They came to a fountain where they took off their clothes and the women sat with the men. ‘Mas’ud,’ the queen called, at which a black slave came up to her and, after they had embraced each other, he lay with her, while the other slaves lay with the slave girls and they spent their time kissing, embracing, fornicating and drinking wine until the end of the day.”

Blimey. And this is just page two, with a couple of beheadings in the bag already. Odd that, for generations in the West, the Arabian Nights was a children’s book, albeit so bowdlerised that there was never much left. Now Penguin has produced this magnificent, unexpurgated edition of the greatest collection of folk tales in the world, each volume running to nearly 1,000 pages, with a beautiful cover design in midnight blue. The translation by Malcolm Lyons, the first complete one since explorer Richard Burton’s in 1885, is plain and lucid, unlike the tortuous, antiquated Victorian version, and the sheer colour and verve of the original stories shine through.

This “ocean of stories” begins with King Shahriyar, having been betrayed by his wife, vowing to sleep with a different virgin every night and then kill her in the morning. But when he takes the smart and sassy Shahrazad to his bed (along with her sister Dunyazad, since she’s around), Shahrazad forestalls their beheading by telling him magical tales. Always keen to hear the next one, the king continually spares her life until the following night.

Besides Shahrazad, however, as Robert Irwin explains in his masterly introductions, the Arabian Nights is a book without an author — or with many thousands. For these are tales that were passed down over centuries, perhaps millenniums, bearing numerous traces of preIslamic culture, and endlessly retold and embellished in the souks and caravanserais of the East. Their influence on the West has been incalculable, from Chaucer to Salman Rushdie. Indeed, much of Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale is straight out of the Arabian Nights. This doesn’t mean that Chaucer read the originals or even knew of their existence. Rather, these marvellous stories had enough innate life to travel on their own, from the backstreets of Baghdad and Cairo to the piazzas of Venice and onward, adapting to their changing environment as they went, like Richard Dawkins’s memes.

And what stories they are, so brimful of energy and lechery, love and cunning, eeriness and death. As a record of oriental low life they are quite invaluable, and often extremely funny. Take the poor old hashish-eater (hashish was known as “the wine of the poor”). After falling to the floor in a stoned swoon, he happily dreams that he is being washed and perfumed by numerous slaves, before having a pretty girl sit in his lap. He is just “pressing her beneath him” when someone shouts, “Wake up, you good-for-nothing!” and he comes round to find himself lying stark naked on the ground with an erection, surrounded by a laughing crowd. “You could have waited until I put it in!” he wails.

Then there’s the young merchant who arrives in Cairo, sells his goods for a tidy “profit of 500%”, and is seduced by a beautiful young girl, who afterwards insists on paying him 15 dinars for the privilege. She does the same the next night, and then on the third she asks him, “Will you let me bring with me a girl who is more beautiful as well as younger than I am, so that she can play with us?” He (surprise surprise) agrees, “And then we got drunk and slept until morning.” So far it sounds like a Lynx advert. But be warned: unlike Lynx ads, these tales have a moral that can be paraphrased as, There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

You can see why the Taliban, or the Muttawa, the religious police of Saudi Arabia, are never going to add the Arabian Nights to their somewhat brusque list of permitted texts. (1 The Koran; 2 The Hadith. Er . . . that’s it.) Even in the broader Islamic world, the Arabian Nights have never been highly valued, and many dismiss them entirely, in the same way that devout Egyptian Muslims show no interest in the architecture or mythology of ancient Egypt. These things belong to Jahiliah, the time of darkness, before the coming of Muhammad, and are therefore by definition worthless. The same goes for the Arabian Nights, with their free and easy ways, unruly djinn, monsters and marvels, hashish and opium, copious wine-drinking and, above all, limitless imagination. Such things are never going to find approval with the puritans.

It is western orientalists, those wicked cultural neocolonialists if you believe Edward Said, who have saved the stories from oblivion. Indeed, for two of the best-known stories included here, Ali Baba and Aladdin, no original Arabic text survives at all. And it is the West that has really taken the stories to heart. Even the titles are liable to send a reader into dangerously incorrect oriental reveries of opium dens, sloe-eyed maidens and caverns gleaming with treasure: The Goldsmith and the Kashmiri Singing Girl, Harun al-Rashid and the Three Slave Girls, or The Island of Waq Waq, where women grow on trees like fruit.

Piety is not a salient characteristic of the tales. There’s far too much unruly life for it to fit a creed. If the tales are set in an Islamic world, it’s Islamic in the way that Chaucer’s world is Christian: religion is a constant but largely benevolent background music, rather than a sinister and omnipresent ideology seeking to impose itself upon every aspect of private life. This is a world of fabulous richness and sensuous pleasure. Here are the contents of a shopping basket: “Syrian apples, Uthmani quinces, Omani peaches, jasmine and water lilies from Syria, autumn cucumbers, lemons, sultani oranges . . . ” Also worldly is the frank celebration of cunning and survival over any more high-minded, abstract notions of virtue. The great thing is to outwit the djinni, get rich quick and marry the pretty girl.

More profound and haunting are those tales which have no clear explanation, and yet resonate deep in the unconscious. Harun al-Rashid is often escaping from the palace and wandering the midnight streets of Baghdad, sometimes in disguise. But in one tale here he takes a boat out on the Tigris, only to see another boat approaching, lit by torches, and, sitting enthroned in the robes of a caliph, a man just like him.

The Arabian Nights is not a book to be read in a week. It is an ocean of stories to be dipped into over a lifetime. And this new Penguin edition is the one to have. Settle back, pour a glass of wine and sail away with Sinbad to the Island of Serendib.

From The Sunday Times December 14, 2008

The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights - the Sunday Times review

A fresh translation of the world’s greatest collection of folk stories restores their colour and verve

Christopher Hart

“In the royal palace there were windows that overlooked Shahriyar’s garden, and as Shah Zaman was looking a door opened and out came 20 slave girls and 20 slaves, in the middle of whom was Shahriyar’s very beautiful wife. They came to a fountain where they took off their clothes and the women sat with the men. ‘Mas’ud,’ the queen called, at which a black slave came up to her and, after they had embraced each other, he lay with her, while the other slaves lay with the slave girls and they spent their time kissing, embracing, fornicating and drinking wine until the end of the day.”

Blimey. And this is just page two, with a couple of beheadings in the bag already. Odd that, for generations in the West, the Arabian Nights was a children’s book, albeit so bowdlerised that there was never much left. Now Penguin has produced this magnificent, unexpurgated edition of the greatest collection of folk tales in the world, each volume running to nearly 1,000 pages, with a beautiful cover design in midnight blue. The translation by Malcolm Lyons, the first complete one since explorer Richard Burton’s in 1885, is plain and lucid, unlike the tortuous, antiquated Victorian version, and the sheer colour and verve of the original stories shine through.

This “ocean of stories” begins with King Shahriyar, having been betrayed by his wife, vowing to sleep with a different virgin every night and then kill her in the morning. But when he takes the smart and sassy Shahrazad to his bed (along with her sister Dunyazad, since she’s around), Shahrazad forestalls their beheading by telling him magical tales. Always keen to hear the next one, the king continually spares her life until the following night.

Besides Shahrazad, however, as Robert Irwin explains in his masterly introductions, the Arabian Nights is a book without an author — or with many thousands. For these are tales that were passed down over centuries, perhaps millenniums, bearing numerous traces of preIslamic culture, and endlessly retold and embellished in the souks and caravanserais of the East. Their influence on the West has been incalculable, from Chaucer to Salman Rushdie. Indeed, much of Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale is straight out of the Arabian Nights. This doesn’t mean that Chaucer read the originals or even knew of their existence. Rather, these marvellous stories had enough innate life to travel on their own, from the backstreets of Baghdad and Cairo to the piazzas of Venice and onward, adapting to their changing environment as they went, like Richard Dawkins’s memes.

And what stories they are, so brimful of energy and lechery, love and cunning, eeriness and death. As a record of oriental low life they are quite invaluable, and often extremely funny. Take the poor old hashish-eater (hashish was known as “the wine of the poor”). After falling to the floor in a stoned swoon, he happily dreams that he is being washed and perfumed by numerous slaves, before having a pretty girl sit in his lap. He is just “pressing her beneath him” when someone shouts, “Wake up, you good-for-nothing!” and he comes round to find himself lying stark naked on the ground with an erection, surrounded by a laughing crowd. “You could have waited until I put it in!” he wails.

Then there’s the young merchant who arrives in Cairo, sells his goods for a tidy “profit of 500%”, and is seduced by a beautiful young girl, who afterwards insists on paying him 15 dinars for the privilege. She does the same the next night, and then on the third she asks him, “Will you let me bring with me a girl who is more beautiful as well as younger than I am, so that she can play with us?” He (surprise surprise) agrees, “And then we got drunk and slept until morning.” So far it sounds like a Lynx advert. But be warned: unlike Lynx ads, these tales have a moral that can be paraphrased as, There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

You can see why the Taliban, or the Muttawa, the religious police of Saudi Arabia, are never going to add the Arabian Nights to their somewhat brusque list of permitted texts. (1 The Koran; 2 The Hadith. Er . . . that’s it.) Even in the broader Islamic world, the Arabian Nights have never been highly valued, and many dismiss them entirely, in the same way that devout Egyptian Muslims show no interest in the architecture or mythology of ancient Egypt. These things belong to Jahiliah, the time of darkness, before the coming of Muhammad, and are therefore by definition worthless. The same goes for the Arabian Nights, with their free and easy ways, unruly djinn, monsters and marvels, hashish and opium, copious wine-drinking and, above all, limitless imagination. Such things are never going to find approval with the puritans.

It is western orientalists, those wicked cultural neocolonialists if you believe Edward Said, who have saved the stories from oblivion. Indeed, for two of the best-known stories included here, Ali Baba and Aladdin, no original Arabic text survives at all. And it is the West that has really taken the stories to heart. Even the titles are liable to send a reader into dangerously incorrect oriental reveries of opium dens, sloe-eyed maidens and caverns gleaming with treasure: The Goldsmith and the Kashmiri Singing Girl, Harun al-Rashid and the Three Slave Girls, or The Island of Waq Waq, where women grow on trees like fruit.

Piety is not a salient characteristic of the tales. There’s far too much unruly life for it to fit a creed. If the tales are set in an Islamic world, it’s Islamic in the way that Chaucer’s world is Christian: religion is a constant but largely benevolent background music, rather than a sinister and omnipresent ideology seeking to impose itself upon every aspect of private life. This is a world of fabulous richness and sensuous pleasure. Here are the contents of a shopping basket: “Syrian apples, Uthmani quinces, Omani peaches, jasmine and water lilies from Syria, autumn cucumbers, lemons, sultani oranges . . . ” Also worldly is the frank celebration of cunning and survival over any more high-minded, abstract notions of virtue. The great thing is to outwit the djinni, get rich quick and marry the pretty girl.

More profound and haunting are those tales which have no clear explanation, and yet resonate deep in the unconscious. Harun al-Rashid is often escaping from the palace and wandering the midnight streets of Baghdad, sometimes in disguise. But in one tale here he takes a boat out on the Tigris, only to see another boat approaching, lit by torches, and, sitting enthroned in the robes of a caliph, a man just like him.

The Arabian Nights is not a book to be read in a week. It is an ocean of stories to be dipped into over a lifetime. And this new Penguin edition is the one to have. Settle back, pour a glass of wine and sail away with Sinbad to the Island of Serendib.

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Arabian Nights - A Fairytale Fantasy

Arabian Nights - A Fairytale Fantasy

A reel of film I found for cheap on ebay.

Haven't watched it yet but will post the film when I get around to filming it!

Monday, December 8, 2008

Mary Zimmerman's revived "The Arabian Nights" in the 510

Review from Variety: (also long live Abu Hassan!)

http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117939135.html?categoryid=33&cs=1

The Arabian Nights

(Berkeley Rep, Berkeley, Calif.; 401 seats; $71 top)

By DENNIS HARVEYA

Berkeley Repertory Theater presentation in association with Kansas City Repertory Theater of a play in two acts written and directed by Mary Zimmerman, created in association with Lookingglass Theater Company, adapted from "The Thousand Nights and One Night" translated by E. Powys Mathers.

With: Ryan Artzberger, Allen Gilmore, Sofia Jean Gomez, Stacey Yen, Barzin Akhavan, Louis Tucci, Noshir Dalal, Pranidhi Varshney, Melina Kalomas, Evan Zes, Nicole Shalhoub, Jesse J. Perez, Alana Arenas, Ramiz Monself, Ari Brand.

First devised during the Gulf War 16 years ago, Mary Zimmerman's revived "The Arabian Nights" arrives at another moment when some positive appreciation of Islam and the Arabic world is particularly welcome. Not to mention nearly three hours of exhilarating, imaginative theatrical escape -- always desirable, but especially soothing at present. Applying the writer-director's signature polyglot style to a few of the "thousand and one" tales, this ingenious entertainment travels to co-producers Kansas City Rep and Chicago's Lookingglass Theater Company's stages after Berkeley Rep; other nonprofits would be wise to keep it on the road indefinitely.

Since discovering his queen's infidelity -- which she pays for with her life -- King Shahryar (Ryan Artzberger) has soured on all womankind, taking a virgin bride every night, then killing her at dawn to ensure he'll never be betrayed again. The realm's marriageable daughters having by now all either died or fled, there's no one left but clever Scheherazade (Sofia Jean Gomez), who puts off her execution by telling cliffhanger stories whose conclusion always requires one more day's reprieve.

Enacted by Zimmerman's multi-cast, multicultural ensemble -- who are required to sing, dance, play instruments and otherwise run on all cylinders throughout -- these tales are ribald and raucously comic in the long (but light-as-a-feather) first half. Her command of wide-ranging tone is such that the act climaxes, hilariously, on the sort of thing a Berkeley Rep audience might normally cross the street to avoid: An epically prolonged fart gag.

After intermission, the stories grow more somber, as Scheherazade seeks to thaw her master's frozen heart. Several tales tacitly chide men for their attitudes toward and treatment of women; the story of Sympathy the Learned contains the evening's most pointed, admiring references to core Muslim beliefs, with allusions to today's extremist "holy war" contortion of those principles.

These "Nights" are a true spectacle, despite the thrust stage being bare of decoration save myriad Persian rugs and a dozen or more hanging lanterns. Zimmerman's highly physical brand of theater is ideally applied here, with everything from sinuous floor-rolling erotica to pantomime camels to full-on production numbers blending into a seamless whole.

There's even room for improvisation, as the "Tale of the Wonderful Bag" has that ownership-contested object's mystery contents described spontaneously by two randomly-chosen cast plaintiffs -- to marvelously absurd results at the performance reviewed.

TJ Gerckens' lighting and Mara Blumenfeld's costumes make notable contributions. But one thing that makes Zimmerman's "Arabian Nights" so special is that it conveys a sumptuousness of aesthetic and imagination, yet might enchant nearly as much if performed by these actors in ordinary street dress on a patch of lawn.

Like Scheherazade herself, the show conjures storytelling magic out of thin air; the true production values here aren't material, but human.

More than one option(Tv) Arabian Nights

(Tv) Arabian Nights

Series Information, Seasons, Credits, Awards

(Film) Arabian Nights

Set, Daniel Ostling; costumes, Mara Blumenfeld; lighting, TJ Gerckens; original music and sound, Andre Pluess & Lookingglass Ensemble; production stage managers, Michael Suenkel, Cynthia Cahill. Opened Nov. 19, 2008. Reviewed Nov. 29. Running time: 2 HOURS, 45 MIN.

http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117939135.html?categoryid=33&cs=1

The Arabian Nights

(Berkeley Rep, Berkeley, Calif.; 401 seats; $71 top)

By DENNIS HARVEYA

Berkeley Repertory Theater presentation in association with Kansas City Repertory Theater of a play in two acts written and directed by Mary Zimmerman, created in association with Lookingglass Theater Company, adapted from "The Thousand Nights and One Night" translated by E. Powys Mathers.

With: Ryan Artzberger, Allen Gilmore, Sofia Jean Gomez, Stacey Yen, Barzin Akhavan, Louis Tucci, Noshir Dalal, Pranidhi Varshney, Melina Kalomas, Evan Zes, Nicole Shalhoub, Jesse J. Perez, Alana Arenas, Ramiz Monself, Ari Brand.

First devised during the Gulf War 16 years ago, Mary Zimmerman's revived "The Arabian Nights" arrives at another moment when some positive appreciation of Islam and the Arabic world is particularly welcome. Not to mention nearly three hours of exhilarating, imaginative theatrical escape -- always desirable, but especially soothing at present. Applying the writer-director's signature polyglot style to a few of the "thousand and one" tales, this ingenious entertainment travels to co-producers Kansas City Rep and Chicago's Lookingglass Theater Company's stages after Berkeley Rep; other nonprofits would be wise to keep it on the road indefinitely.

Since discovering his queen's infidelity -- which she pays for with her life -- King Shahryar (Ryan Artzberger) has soured on all womankind, taking a virgin bride every night, then killing her at dawn to ensure he'll never be betrayed again. The realm's marriageable daughters having by now all either died or fled, there's no one left but clever Scheherazade (Sofia Jean Gomez), who puts off her execution by telling cliffhanger stories whose conclusion always requires one more day's reprieve.

Enacted by Zimmerman's multi-cast, multicultural ensemble -- who are required to sing, dance, play instruments and otherwise run on all cylinders throughout -- these tales are ribald and raucously comic in the long (but light-as-a-feather) first half. Her command of wide-ranging tone is such that the act climaxes, hilariously, on the sort of thing a Berkeley Rep audience might normally cross the street to avoid: An epically prolonged fart gag.

After intermission, the stories grow more somber, as Scheherazade seeks to thaw her master's frozen heart. Several tales tacitly chide men for their attitudes toward and treatment of women; the story of Sympathy the Learned contains the evening's most pointed, admiring references to core Muslim beliefs, with allusions to today's extremist "holy war" contortion of those principles.

These "Nights" are a true spectacle, despite the thrust stage being bare of decoration save myriad Persian rugs and a dozen or more hanging lanterns. Zimmerman's highly physical brand of theater is ideally applied here, with everything from sinuous floor-rolling erotica to pantomime camels to full-on production numbers blending into a seamless whole.

There's even room for improvisation, as the "Tale of the Wonderful Bag" has that ownership-contested object's mystery contents described spontaneously by two randomly-chosen cast plaintiffs -- to marvelously absurd results at the performance reviewed.

TJ Gerckens' lighting and Mara Blumenfeld's costumes make notable contributions. But one thing that makes Zimmerman's "Arabian Nights" so special is that it conveys a sumptuousness of aesthetic and imagination, yet might enchant nearly as much if performed by these actors in ordinary street dress on a patch of lawn.

Like Scheherazade herself, the show conjures storytelling magic out of thin air; the true production values here aren't material, but human.

More than one option(Tv) Arabian Nights

(Tv) Arabian Nights

Series Information, Seasons, Credits, Awards

(Film) Arabian Nights

Set, Daniel Ostling; costumes, Mara Blumenfeld; lighting, TJ Gerckens; original music and sound, Andre Pluess & Lookingglass Ensemble; production stage managers, Michael Suenkel, Cynthia Cahill. Opened Nov. 19, 2008. Reviewed Nov. 29. Running time: 2 HOURS, 45 MIN.

postcolonial 1001 nights

This is a dissertation? Essay?

PDF Link: http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/dissertations/2003-0310-101002/pt2c3.pdf

On the following topic:

"Githa Hariharan’s When Dreams Travel (1999) is a re-writing of The Arabian

Nights’ Entertainments or The Thousand and One Nights, as these texts became known in

the West via a French translation."

With the following questions as guides:

"And what is there in this rewriting of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (an

alternative name of The Thousand and One Nights) for the postcolonial dimension of this research? Why would Githa Hariharan find important to decolonise such a text? What is at stake in such an enterprise?"

Frankly there are too many generalizations about the Nights in this essay although that's what seems to happen when people start applying theories willy nilly to fit their arguments. Also it seems that the Nights are still alive and well and can be flexible enough to fit any kind of argument or theory or re/translat(ion).

PDF Link: http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/dissertations/2003-0310-101002/pt2c3.pdf

On the following topic:

"Githa Hariharan’s When Dreams Travel (1999) is a re-writing of The Arabian

Nights’ Entertainments or The Thousand and One Nights, as these texts became known in

the West via a French translation."

With the following questions as guides:

"And what is there in this rewriting of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (an

alternative name of The Thousand and One Nights) for the postcolonial dimension of this research? Why would Githa Hariharan find important to decolonise such a text? What is at stake in such an enterprise?"

Frankly there are too many generalizations about the Nights in this essay although that's what seems to happen when people start applying theories willy nilly to fit their arguments. Also it seems that the Nights are still alive and well and can be flexible enough to fit any kind of argument or theory or re/translat(ion).

Friday, December 5, 2008

Breaking Wind

How Abu Hassan Brake Wind - I read somewhere and need to re-find it, I think in Robert Irwin's book on the Nights or an article, that this story's first appearance was in Burton's edition and no previous mention of it or version before Burton has ever been found, in Arabic or any other language.

It's a great Burton-esque guy/teenage boy story about a groom who has gas at the wrong time and has to run away from his country because of his shame.

What is really funny about it is that Dawood includes it in his Penguin English version of the Nights, after bashing Burton in his introduction...

Here's a mention of the story being turned into a joke about the Queen herself (maybe a true story - or common English joke - that Burton picked up and turned into an "Arabian Night"??):

http://www.newstatesman.com/books/2008/12/jokes-holt-history-book

There is a nod to The Arabian Nights, but even this is slight, and comes through an English joke told by John Aubrey: "[The] Earle of Oxford, making of his low obeisance to Queen Elizabeth, happened to let a Fart, at which he was so abashed and ashamed that he went to Travell, 7 yeares. On his returne the Queen welcomed him home, and sayd, My Lord, I had forgott the Fart." This, Holt remarks, makes an even earlier appearance in the story "How Abu Hassan Brake Wind".

- The article this is taken from is a review of this recently released book:

Stop Me If You've Heard This: a History and Philosophy of Jokes

Jim Holt - Profile Books

It's a great Burton-esque guy/teenage boy story about a groom who has gas at the wrong time and has to run away from his country because of his shame.

What is really funny about it is that Dawood includes it in his Penguin English version of the Nights, after bashing Burton in his introduction...

Here's a mention of the story being turned into a joke about the Queen herself (maybe a true story - or common English joke - that Burton picked up and turned into an "Arabian Night"??):

http://www.newstatesman.com/books/2008/12/jokes-holt-history-book

There is a nod to The Arabian Nights, but even this is slight, and comes through an English joke told by John Aubrey: "[The] Earle of Oxford, making of his low obeisance to Queen Elizabeth, happened to let a Fart, at which he was so abashed and ashamed that he went to Travell, 7 yeares. On his returne the Queen welcomed him home, and sayd, My Lord, I had forgott the Fart." This, Holt remarks, makes an even earlier appearance in the story "How Abu Hassan Brake Wind".

- The article this is taken from is a review of this recently released book:

Stop Me If You've Heard This: a History and Philosophy of Jokes

Jim Holt - Profile Books

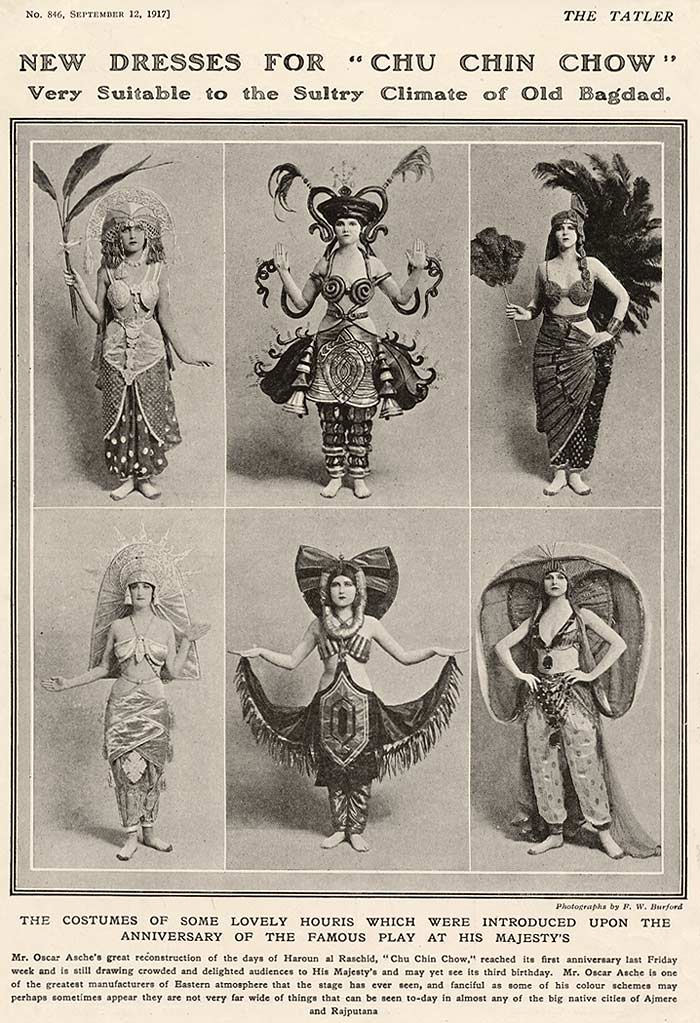

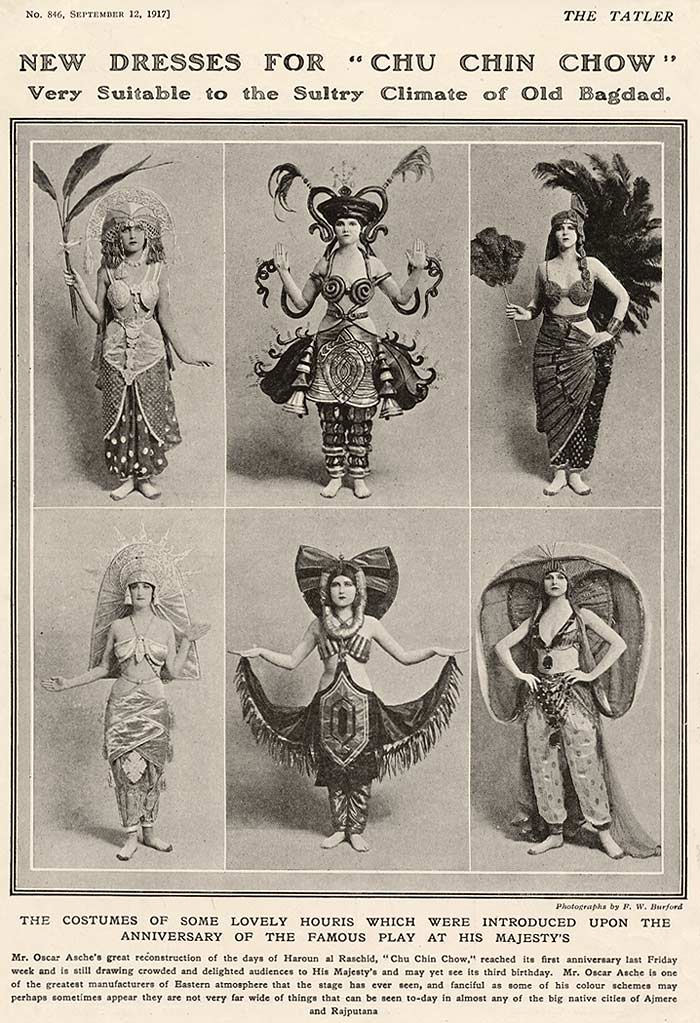

Chu Chin Chow

I'll have to look into something about the Nights being a stage phenomenon, particularly in the early 20th century. Something was all the rage with the Nights on stage.

A 2008 production of Chu Chin Chow (what a name!) in the UK spurred my looking into the topic.

From wikipedia: (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chu_Chin_Chow)

The success of the "Arabian Nights" production Kismet (a 1911 play by Edward Knoblock, upon which the 1953 musical is based) inspired Oscar Asche to write and produce Chu Chin Chow. Asche also played the lead role of Abu Hasan, leader of the forty thieves (the "Chu Chin Chow" of the title is actually the robber chief himself impersonating one of his victims). Besides Asche, the production starred his wife, Lily Brayton, and Courtice Pounds.

- Apparently it was a hugely successful play (CCC)

Here's the new review from the UK: http://www.southportvisiter.co.uk/southport-entertainment/2008/12/05/una-voce-opera-company-do-chu-chin-chow-at-southport-arts-centre-101022-22407514/

Una Voce Opera Company do Chu Chin Chow at Southport Arts Centre

Dec 5 2008 by Kathryn Carr, Southport Visiter

Opera Teaser

OPERA fans can escape the winter chill with a magical, musical tale of the East, courtesy of Una Voce Opera Company.

The company is proud to present its Christmas production, Chu Chin Chow, one of the longest-running musicals in history.

Written by Oscar Asche with music composed by Frederic Norton in 1916, the show is based on the Arabian Nights Tale of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and includes musicalfavourites such as The Cobbler’s Song and Any Time’s Kissing-time.

Clare Hyams and Eunice Woof MBE will share the role of Mahbubah, while the visiting star of the show will be Jane Zoo, from Hong Kong, who will sing the role of Marjanah (originally made famous by Anna May Wong).

Jane, who was born in Beijing, completed her undergraduate training in 2005 at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts.

She has just finished postgraduate studies at the Royal Northern College of Music, studying with Sandra Dugdale.

While at the college Jane played the role of the Hen in The Cunning Little Vixen.

In opera excerpts she performed the roles of Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Romilda in Serse, Lucia in The Rape of Lucretia and the title rôle in Lakmé.

Jane was in the premiere of Fei Jia Dong, a contemporary multimedia music theatre piece at the Arts Centre in Hong Kong.

She also appeared as an opera singer in Kubert Leung’s film Wonderful Times and sang the title song.

The talented star was a semi-finalist in the Stuart Burrows International Singing Competition in Wales, and was invited as a guest artist to sing in the London Week of Peace concert in Trafalgar Square.

She also sang in the Great Elm Vocal Awards finalist concert in the Wigmore Hall.

Jane has recently signed a recording contract with Shlepp Records.

Chu Chin Chow marks Jane’s début guest appearance with Una Voce Opera Company.

Performances are at Southport Arts Centre until Saturday, December 6. Tickets are £10-£16.50.

Concessions and group rates are available. Tickets to the 2.30pm Saturday matinee are £8.

To book, call Southport Arts Centre box office on 01704 540011, or visit www.seftonarts.co.uk

A 2008 production of Chu Chin Chow (what a name!) in the UK spurred my looking into the topic.

From wikipedia: (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chu_Chin_Chow)

The success of the "Arabian Nights" production Kismet (a 1911 play by Edward Knoblock, upon which the 1953 musical is based) inspired Oscar Asche to write and produce Chu Chin Chow. Asche also played the lead role of Abu Hasan, leader of the forty thieves (the "Chu Chin Chow" of the title is actually the robber chief himself impersonating one of his victims). Besides Asche, the production starred his wife, Lily Brayton, and Courtice Pounds.

- Apparently it was a hugely successful play (CCC)

Here's the new review from the UK: http://www.southportvisiter.co.uk/southport-entertainment/2008/12/05/una-voce-opera-company-do-chu-chin-chow-at-southport-arts-centre-101022-22407514/

Una Voce Opera Company do Chu Chin Chow at Southport Arts Centre

Dec 5 2008 by Kathryn Carr, Southport Visiter

Opera Teaser

OPERA fans can escape the winter chill with a magical, musical tale of the East, courtesy of Una Voce Opera Company.

The company is proud to present its Christmas production, Chu Chin Chow, one of the longest-running musicals in history.

Written by Oscar Asche with music composed by Frederic Norton in 1916, the show is based on the Arabian Nights Tale of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and includes musicalfavourites such as The Cobbler’s Song and Any Time’s Kissing-time.

Clare Hyams and Eunice Woof MBE will share the role of Mahbubah, while the visiting star of the show will be Jane Zoo, from Hong Kong, who will sing the role of Marjanah (originally made famous by Anna May Wong).

Jane, who was born in Beijing, completed her undergraduate training in 2005 at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts.

She has just finished postgraduate studies at the Royal Northern College of Music, studying with Sandra Dugdale.

While at the college Jane played the role of the Hen in The Cunning Little Vixen.

In opera excerpts she performed the roles of Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Romilda in Serse, Lucia in The Rape of Lucretia and the title rôle in Lakmé.

Jane was in the premiere of Fei Jia Dong, a contemporary multimedia music theatre piece at the Arts Centre in Hong Kong.

She also appeared as an opera singer in Kubert Leung’s film Wonderful Times and sang the title song.

The talented star was a semi-finalist in the Stuart Burrows International Singing Competition in Wales, and was invited as a guest artist to sing in the London Week of Peace concert in Trafalgar Square.

She also sang in the Great Elm Vocal Awards finalist concert in the Wigmore Hall.

Jane has recently signed a recording contract with Shlepp Records.

Chu Chin Chow marks Jane’s début guest appearance with Una Voce Opera Company.

Performances are at Southport Arts Centre until Saturday, December 6. Tickets are £10-£16.50.

Concessions and group rates are available. Tickets to the 2.30pm Saturday matinee are £8.

To book, call Southport Arts Centre box office on 01704 540011, or visit www.seftonarts.co.uk

Burton the Muslim

Burton says he is a Muslim here:

"Finally I went to Meccah not as a Christian, but as a Moslem."

In a letter to the editor called "Unexplored Syria." The Academy 2 Jun. 1873: 217.

"Finally I went to Meccah not as a Christian, but as a Moslem."

In a letter to the editor called "Unexplored Syria." The Academy 2 Jun. 1873: 217.

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

A thousand and one nights at the panto

An old article but a good overview of the Nights and its relationship to stage and screen (and mention of the cool pinball machine), by Robert Irwin:

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/a-thousand-and-one-nights-at-the-panto-620893.html

A thousand and one nights at the panto

How did the yarns spun in the alleys of medieval Cairo and Damascus turn into the pantomime and movie tales known to every child in the West? Robert Irwin tells the amazing story of the Arabian Nights

Saturday, 22 December 2001

It is getting harder and harder to find good pinball machines in London. I doubt if it is still there, but a few years ago The Man in the Moon pub in the King's Road, Chelsea, west London, used to have one of the classic Williams machines. This was the "Tales of the Arabian Nights" model. One looked down on a (mostly cinematic) iconography of the Nights, divorced from particular Arabic stories, spread out on the machine's gaudy playboard between the flippers and the buffers. This visual clutter, suggestive of opulence, adventure and magic, will register with people who have never opened a volume of the Nights: the Roc's egg, harem girls in diaphanous trousers, scimitars, genies, minarets, the Cyclops, the prince disguised as a beggar, the basket full of serpents, the rope that turns into a ladder, and the all-seeing eye.

These days The Arabian Nights (or The Thousand and One Nights) is generally considered a book for children. It was not always so. The audience for the medieval Arabic story collection probably consisted of male adults. The earliest substantially surviving manuscript is Egyptian, and probably dates from the 14th or 15th century. It perhaps represents the repertoire of a professional storyteller.

Though manuscripts circulated in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere, the collection was not well-known until the 18th century. Then a scholarly French antiquarian and classicist took Europe by storm with his bestselling translation into French. Antoine Galland had served as secretary of the French embassy in Istanbul in the 1690s. His special mission in Istanbul was to collect documents from Eastern Christian churches with a bearing on the Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist, but Galland's interests ran wider. Having learnt Arabic, he collected manuscripts of all kinds.

In 1701 he published a translation of the stories of Sinbad the Sailor. These stories never formed part of the early manuscripts of the Nights. However, Galland's translation was an instant success and in 1704 he started to publish translations of the Nights stories that he had been working on to pass away the long dark evenings. The Sinbad stories thereafter were assimilated into the collection of Nights stories, the supposed repertoire of the storytelling Queen Scheherezade.

Galland's Les Milles et Une Nuits was a hit with both courtiers and scholars. His versions of the stories, as well as his learned glosses, offered a window on an oriental way of life, as well as a new and unfamiliar pool of storytelling motifs. Other writers set about producing adaptations, imitations and satires of oriental tales.

Even before Galland had finished his French translation, the early parts were being translated into other European languages. From the first decade of the 18th century, Grub Street versions circulated in Britain. They were to exercise a strong influence on such diverse writers as Joseph Addison, Samuel Johnson, Horace Walpole, William Beckford and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In 1838-41, Edward William Lane produced a fairly comprehensive translation made directly from the Arabic. However, Lane prudishly omitted episodes and stories that he judged improper. In 1885-8, the explorer Sir Richard Burton produced a translation that not only included all the bawdy bits omitted by Lane, but exaggerated the obscenity in some tales.

The early pantomime versions of Aladdin, Sinbad and other stories were adapted from unscholarly chap-book versions. The first pantomime of Aladdin was staged in 1788, but the most successful version was a burlesque scripted by H J Byron in 1861, Aladdin or the Wonderful Scamp. Byron's laboriously rhymed and pun-laden Aladdin was the first to feature Widow Twankay, (the reference being to a kind of green tea from Tun-chi in China).

In the 19th century, music-hall turns and allusions to contemporary events were added to the stories. In 1882 the staging of Sinbad the Sailor was adapted to celebrate Sir Garnett Wolseley's victory over Arabi Pasha in Egypt. A toy-theatre version of Aladdin or the Wonderful Lamp appeared as early as 1811. Paper cut-outs produced for this and other toy-theatre scenarios faithfully recorded the sets and costumes of early stage productions.

The early silent films also serve as a kind of record of stage versions. The history of the Nights on film is nearly as old as film the history of film itself. In 1902, Thomas Edison produced a film version of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, directed by the comic actor Ferdinand Zecca. This was based on a popular stage production and used dancers from the Paris Opera. Soon after came Georges Méliès' Palais des Mille et Une Nuits, (1905), in which the oriental setting served as a licence for special effects, as well as display of the plump legs of a troupe of chorines. Zecca did an Aladdin or the Marvelous Lamp in 1906. Thereafter the floodgates opened.

There is a Popeye version of Aladdin, a Douglas Fairbanks junior version of Sinbad the Sailor, and Phil Silvers starred in A Thousand and One Nights (1945) as the bespectacled Abdullah the Touched One. There have been Nights films starring Dorothy Lamour, Abbott & Costello, Eddy Cantor, Mickey Mouse, Gene Kelly, Steve Reeves, Micky Rooney, Christopher Lee, Gipsy Rose Lee, Tom Baker, Patrick Troughton, Krazy Kat, Woody Woodpecker, Peter Ustinov, Tony Curtis, Lucille Ball, Bugs Bunny and Elvis Presley. Hundreds of Arabian Nights have been made, and most have been deservedly forgotten.

But among the rich mulch of mock-exotic trash there have also been some masterpieces, including some of the classic silent films. Ernst Lubitsch's Sumurun (1920) reproduced Max Reinhardt's pantomime fantasy, which was in turn very loosely based on the Nights story of The Hunchback. Lubitsch himself hammed it up as the erotically thwarted hunchback. In 1926 Lotte Reiniger completed Die Abenteur des Prinzen Achmed. This film, with its delicately cut silhouette figures, was the world's first full-length animation picture. (It has recently been released as a video by the British Film Institute.)

Some of the most artistic film adaptations were produced in Germany and, when Douglas Fairbanks senior started to plan his masterpiece, The Thief of Bagdad, he went to Germany to study the works of such German film-makers as Lubitsch and Fritz Lang. The look of Fairbanks's film, released in 1924, has clearly been influenced by the design and effects of earlier German productions. However, Fairbanks gave his adaptation of "Prince Ahmed and the Peri Banou" a characteristically American stress on the work ethic: "Happiness has to be earned". The original medieval Arab storytellers were quite happy with the notion of unearned happiness.

Alexander Korda's 1940 production of The Thief of Bagdad, though it borrowed the Fairbanks title, had a quite different plot and other preoccupations. The story made intensive use of special effects and spectacular colour photography to create the land of oriental enchantment that might be imagined by a child. That outstanding director Michael Powell worked on it and Conrad Veidt, better known as Major Strasser in Casablanca, was a superbly villainous vizier.

Veidt's interpretation has influenced the performances of almost all subsequent villainous viziers, including those in the swashbuckling Ray Harryhausen Sinbad films and the Disney animated Aladdin. The Disney Aladdin (1992) has more wit and energy, as well as a more logical plot, than the original story found in Galland.

However, perhaps the best and most intelligent of Nights films, Il fiore della Mille e una notte (1974), was directed by the Marxist intellectual, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini filmed unknown actors in spectacular location shots. He sacrificed none of the eroticism of the original tales and, unlike earlier film-makers, he preserved the bemusing story within-a-within-a-story structure. As he observed in an epigraph to the film, "The truth is to be found not in one dream, but in many dreams".

Robert Irwin is the author of 'The Arabian Nights: a companion' (Penguin). 'The Arabian Nights', translated by Husain Haddawy, is an Everyman's Library hardback; there is also a Penguin Classics 'Tales from the Thousand and One Nights', trans N J Dawood. 'The Golden Voyage of Sinbad' is on Channel 4 on Christmas Eve, and 'Aladdin and the King of Thieves' on BBC 1 on Boxing Day

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/a-thousand-and-one-nights-at-the-panto-620893.html

A thousand and one nights at the panto

How did the yarns spun in the alleys of medieval Cairo and Damascus turn into the pantomime and movie tales known to every child in the West? Robert Irwin tells the amazing story of the Arabian Nights

Saturday, 22 December 2001

It is getting harder and harder to find good pinball machines in London. I doubt if it is still there, but a few years ago The Man in the Moon pub in the King's Road, Chelsea, west London, used to have one of the classic Williams machines. This was the "Tales of the Arabian Nights" model. One looked down on a (mostly cinematic) iconography of the Nights, divorced from particular Arabic stories, spread out on the machine's gaudy playboard between the flippers and the buffers. This visual clutter, suggestive of opulence, adventure and magic, will register with people who have never opened a volume of the Nights: the Roc's egg, harem girls in diaphanous trousers, scimitars, genies, minarets, the Cyclops, the prince disguised as a beggar, the basket full of serpents, the rope that turns into a ladder, and the all-seeing eye.

These days The Arabian Nights (or The Thousand and One Nights) is generally considered a book for children. It was not always so. The audience for the medieval Arabic story collection probably consisted of male adults. The earliest substantially surviving manuscript is Egyptian, and probably dates from the 14th or 15th century. It perhaps represents the repertoire of a professional storyteller.

Though manuscripts circulated in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere, the collection was not well-known until the 18th century. Then a scholarly French antiquarian and classicist took Europe by storm with his bestselling translation into French. Antoine Galland had served as secretary of the French embassy in Istanbul in the 1690s. His special mission in Istanbul was to collect documents from Eastern Christian churches with a bearing on the Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist, but Galland's interests ran wider. Having learnt Arabic, he collected manuscripts of all kinds.

In 1701 he published a translation of the stories of Sinbad the Sailor. These stories never formed part of the early manuscripts of the Nights. However, Galland's translation was an instant success and in 1704 he started to publish translations of the Nights stories that he had been working on to pass away the long dark evenings. The Sinbad stories thereafter were assimilated into the collection of Nights stories, the supposed repertoire of the storytelling Queen Scheherezade.

Galland's Les Milles et Une Nuits was a hit with both courtiers and scholars. His versions of the stories, as well as his learned glosses, offered a window on an oriental way of life, as well as a new and unfamiliar pool of storytelling motifs. Other writers set about producing adaptations, imitations and satires of oriental tales.

Even before Galland had finished his French translation, the early parts were being translated into other European languages. From the first decade of the 18th century, Grub Street versions circulated in Britain. They were to exercise a strong influence on such diverse writers as Joseph Addison, Samuel Johnson, Horace Walpole, William Beckford and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In 1838-41, Edward William Lane produced a fairly comprehensive translation made directly from the Arabic. However, Lane prudishly omitted episodes and stories that he judged improper. In 1885-8, the explorer Sir Richard Burton produced a translation that not only included all the bawdy bits omitted by Lane, but exaggerated the obscenity in some tales.

The early pantomime versions of Aladdin, Sinbad and other stories were adapted from unscholarly chap-book versions. The first pantomime of Aladdin was staged in 1788, but the most successful version was a burlesque scripted by H J Byron in 1861, Aladdin or the Wonderful Scamp. Byron's laboriously rhymed and pun-laden Aladdin was the first to feature Widow Twankay, (the reference being to a kind of green tea from Tun-chi in China).

In the 19th century, music-hall turns and allusions to contemporary events were added to the stories. In 1882 the staging of Sinbad the Sailor was adapted to celebrate Sir Garnett Wolseley's victory over Arabi Pasha in Egypt. A toy-theatre version of Aladdin or the Wonderful Lamp appeared as early as 1811. Paper cut-outs produced for this and other toy-theatre scenarios faithfully recorded the sets and costumes of early stage productions.

The early silent films also serve as a kind of record of stage versions. The history of the Nights on film is nearly as old as film the history of film itself. In 1902, Thomas Edison produced a film version of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, directed by the comic actor Ferdinand Zecca. This was based on a popular stage production and used dancers from the Paris Opera. Soon after came Georges Méliès' Palais des Mille et Une Nuits, (1905), in which the oriental setting served as a licence for special effects, as well as display of the plump legs of a troupe of chorines. Zecca did an Aladdin or the Marvelous Lamp in 1906. Thereafter the floodgates opened.

There is a Popeye version of Aladdin, a Douglas Fairbanks junior version of Sinbad the Sailor, and Phil Silvers starred in A Thousand and One Nights (1945) as the bespectacled Abdullah the Touched One. There have been Nights films starring Dorothy Lamour, Abbott & Costello, Eddy Cantor, Mickey Mouse, Gene Kelly, Steve Reeves, Micky Rooney, Christopher Lee, Gipsy Rose Lee, Tom Baker, Patrick Troughton, Krazy Kat, Woody Woodpecker, Peter Ustinov, Tony Curtis, Lucille Ball, Bugs Bunny and Elvis Presley. Hundreds of Arabian Nights have been made, and most have been deservedly forgotten.

But among the rich mulch of mock-exotic trash there have also been some masterpieces, including some of the classic silent films. Ernst Lubitsch's Sumurun (1920) reproduced Max Reinhardt's pantomime fantasy, which was in turn very loosely based on the Nights story of The Hunchback. Lubitsch himself hammed it up as the erotically thwarted hunchback. In 1926 Lotte Reiniger completed Die Abenteur des Prinzen Achmed. This film, with its delicately cut silhouette figures, was the world's first full-length animation picture. (It has recently been released as a video by the British Film Institute.)

Some of the most artistic film adaptations were produced in Germany and, when Douglas Fairbanks senior started to plan his masterpiece, The Thief of Bagdad, he went to Germany to study the works of such German film-makers as Lubitsch and Fritz Lang. The look of Fairbanks's film, released in 1924, has clearly been influenced by the design and effects of earlier German productions. However, Fairbanks gave his adaptation of "Prince Ahmed and the Peri Banou" a characteristically American stress on the work ethic: "Happiness has to be earned". The original medieval Arab storytellers were quite happy with the notion of unearned happiness.